About the Audit

As one of its first steps, the Walking in the Footsteps project commissioned research into commemorations that already exist in southeast Nebraska. In consultation with project co-directors, the research team focused on historical markers sponsored by the Nebraska State Historical Society. This program started in the late 1950s with the first marker constructed in 1961. The historical markers are all engraved metal with the identifiable seal of Nebraska at the top. Each includes a commemorative narrative that allowed our project to gain insight into what topics and individuals garnered the most attention in the region. Most commemorative markers have been initiated and funded by community organizations, in partnership with the state.

Prior to this period, communities erected other historical monuments and markers, usually in granite, in their communities, but they did not have the official backing of the state. Jeff Barnes details these in his book, Cut in Stone, Cast in Bronze. Other entities, including the National Park Service, Nebraska Game and Parks, and Nebraska Department of Transportation, have erected some monuments at rest areas and other locations.

The Walking in the Footsteps project wanted to gain a sense of whether historical monuments in southeast Nebraska included the history of the Otoe-Missouria people, the sovereign Indigenous nation that called the area home for hundreds of years, gradually ceded the land to the U.S. government through two treaties in the 1800s, and gave the state its name, Nyi Brathge (Nebraska). We also wanted to find out how these historical markers dealt with other Indigenous histories in the region.

We were inspired to conduct this regional audit based on the National Monument Audit that was produced in partnership with the Mellon Foundation by the Monument Lab, a Philadelphia-based non-profit art and history studio that cultivates and facilitates critical conversations around the past, present, and future of monuments. Their national audit collected data on half a million monuments and focused on some 50,000 statues or monoliths installed or maintained in a public space with the authority of a government agency or institution as well as nonconventional monument objects like buildings, bridges, streets, historic markers, and place names. The National Monument Audit included 31 monuments in all of Nebraska, only eight of which were historical markers. They mentioned six markers in southeast Nebraska. Our audit is much more modest than the national effort and covers a much smaller area, but it allows for a deeper dive into the 363 modern Nebraska State Historical Society markers, the 170 earlier granite monuments, and nine additional monuments at highway rest areas and other locations.

Key Findings

1. The overwhelming majority of historical markers in southeast Nebraska focus on settlers and their achievements and celebrate the colonization of the area.

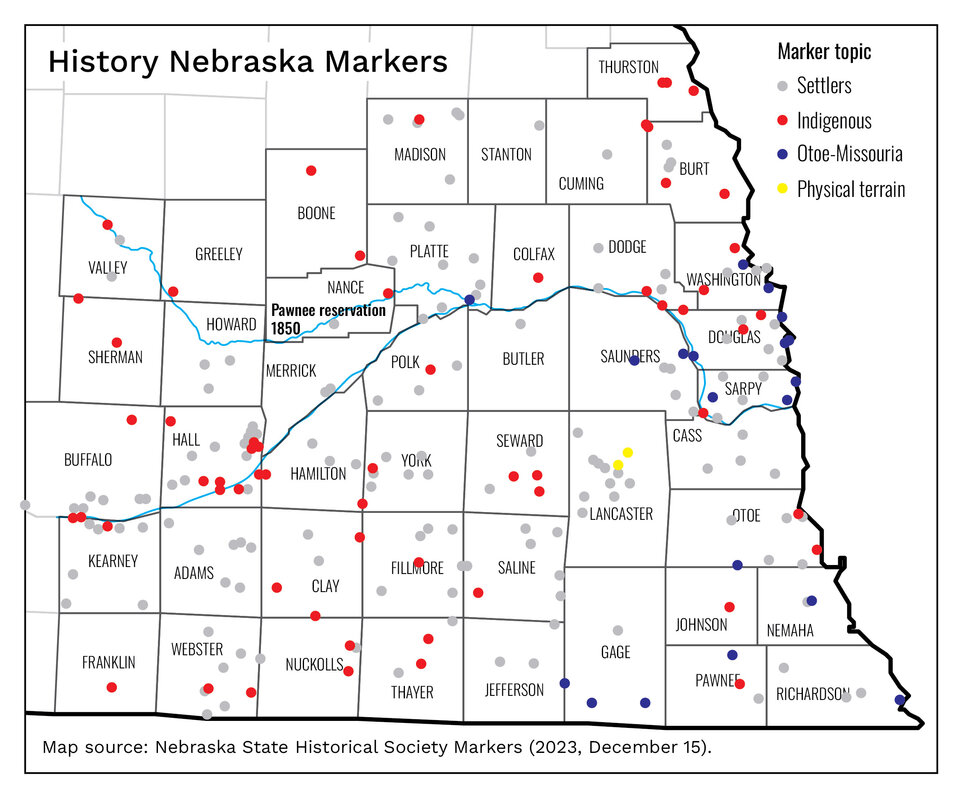

Of the 363 modern historical markers, 259 (72% percent) focus only on settlers, people of non-Indigenous descent who migrated to southeast Nebraska. 100 markers (27.5%) mention Indigenous people. Only one marker, in Lancaster County, does not commemorate people. Instead, it mentions glacial activity. Three markers offer no narrative.

2. When markers do mention Indigenous people, it is nearly always in relation to settlers and/or from the perspective of settlers.

None of the 100 modern historical markers that mention Indigenous people tell their story without also mentioning settlers. Historical markers thus tell a partial history of Indigenous people that focuses entirely on their interactions with settlers. The earlier granite markers, erected by organizations such as the Daughters of the American Revolution, focused even more on settlers. They rarely mention specific Native nations, and when they do feature Indigenous people, it is usually as threats to settlers.

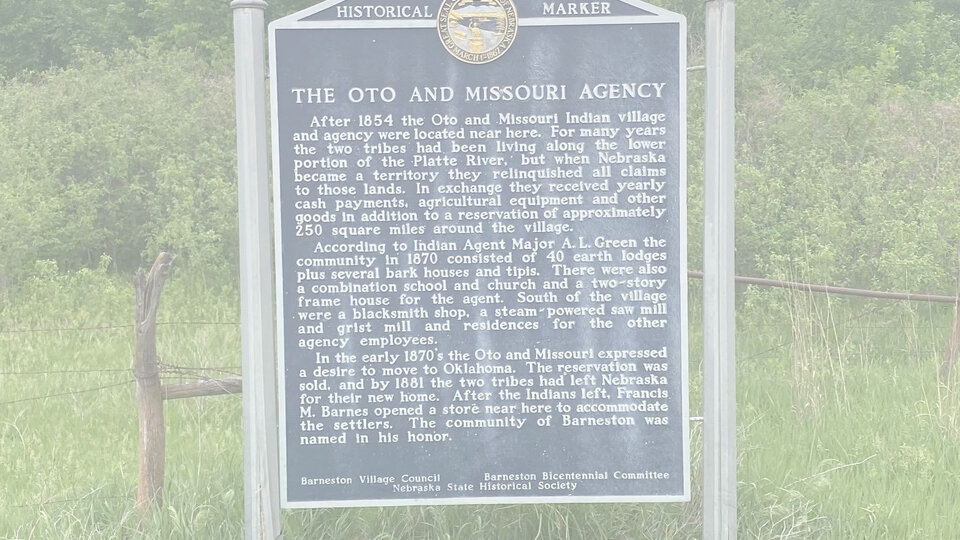

3. The Otoe-Missouria Tribe, which occupied the area for hundreds of years, are mentioned on just 5% of historical markers, and often only in reference to Lewis and Clark.

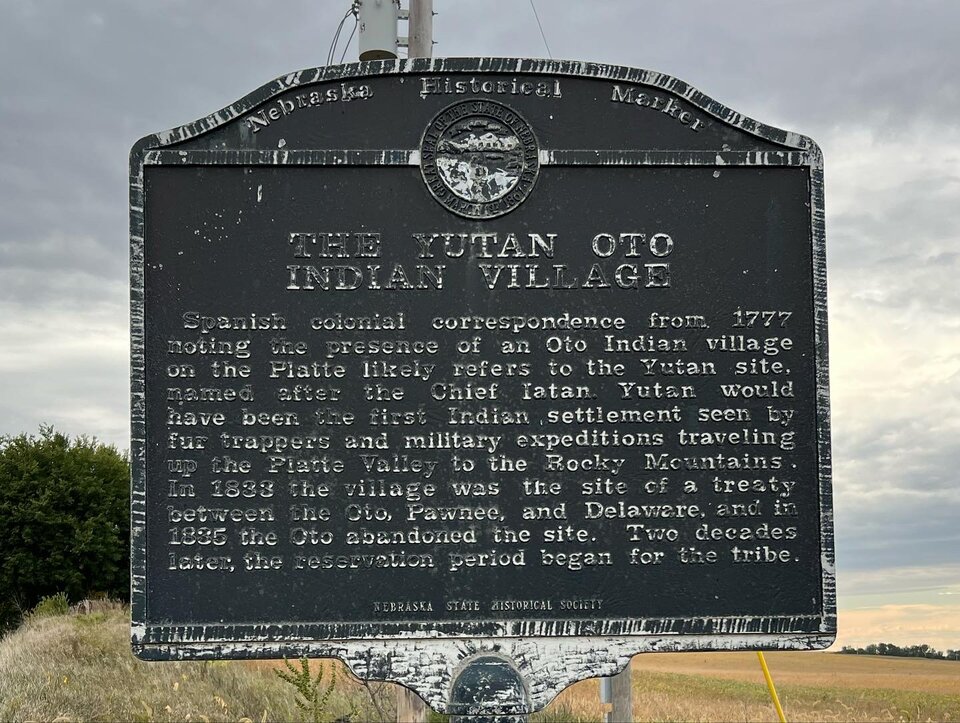

Of the 100 modern historical markers that mentioned Indigenous people, only 21 cover some aspect of Otoe-Missouria history. If there were not so many markers celebrating Lewis and Clark (8 or 38%), there would only be 13 markers that mention the Otoe-Missouria tribe. None of the earlier granite monuments mentioned the Otoe-Missouria. Markers nearly always spell Otoe as Oto and Missouria as Missouri, which shows lack of consultation with the tribe about how it represents itself in contemporary times.

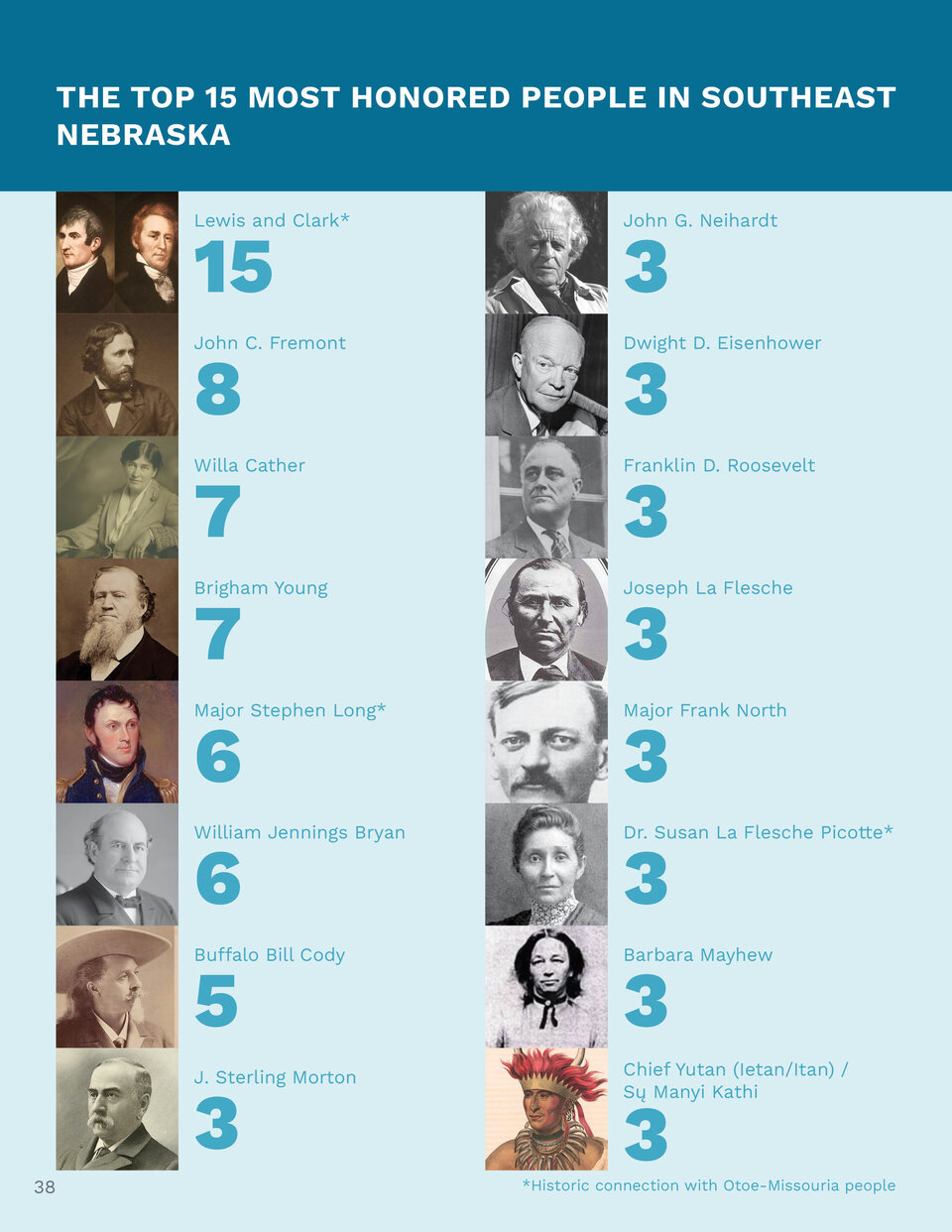

Highlighted Individuals

Of the top five individuals who are commemorated, four are men who spent minimal time in southeast Nebraska. Three (Lewis and Clark, Fremont, and Long) were explorers with military experience charged with surveying the area for future colonization and settlement. Brigham Young led a party of Latter-Day Saints through the area on the way to settling in Utah. Other than the Indigenous persons on the list, only six of the settlers in the top 15 spent any significant time in Nebraska as residents: Willa Cather, William Jennings Bryan, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, J. Sterling Morton, John G. Neihardt, and Barbara Mayhew.

Ironically, then, even Nebraskans are not focused on honoring the individual settlers who stayed in the area. This reinforces the notion that the state is merely a place to pass through. Interestingly, many of the top 15 memorials could have brought out Otoe-Missouria connections, but instead only focused on the settler narrative. For example, the explorer Stephen Long collected word lists from Otoe-Missouria and other tribes. A member of his expedition offered the first European detail drawings of individual Otoe-Missouria people. Buffalo Bill Cody hired several Otoe-Missouria as part of his Wild West Show.

The top 15 include just one Otoe-Missouria individual, Chief Sų Manyi Kathi (Yutan), who is mentioned in three historical markers, though not by his Otoe-Missouria name. In all cases, the markers only note that the Indian village of Yutan and subsequent settler town of Yutan were named for the chief. One marker notes Yutan was chief from about 1830 until his death in 1837 but otherwise none of these markers include any further information about the chief’s or tribe’s history. Only two other Native individuals — Joseph La Flesche and his daughter Susan LaFlesche Picotte, of the Omaha Tribe — are featured in historical markers.

With 15 examples, Lewis and Clark gain the lion’s share of attention among the modern historical markers. Interestingly, they garner only a passing mention in the earlier granite markers. Only one early marker in Rulo concentrates on them. Nationally, Lewis and Clark have nearly 40 monuments, second only to Christopher Columbus.

Coming Soon

Updated historical markers